How to Calculate Correct Grip Length (With Real-World Examples)

When it comes to bolted flange joints, grip length is one of the most overlooked, but absolutely critical, factors for achieving proper preload, gasket compression, and joint integrity. In this post, we'll break down what grip length really means, why it matters, how to calculate it properly, and common mistakes to avoid. We'll also include real-world examples.

Bolt Tension vs. Bolt Stress vs. Clamp Load: What Engineers Actually Mean

Plant engineers and maintenance supervisors often hear terms like bolt tension, bolt stress, and clamp load used in discussions about bolted joints and flange assemblies. These terms are related but not identical – and mixing them up can lead to confusion or even maintenance mistakes.

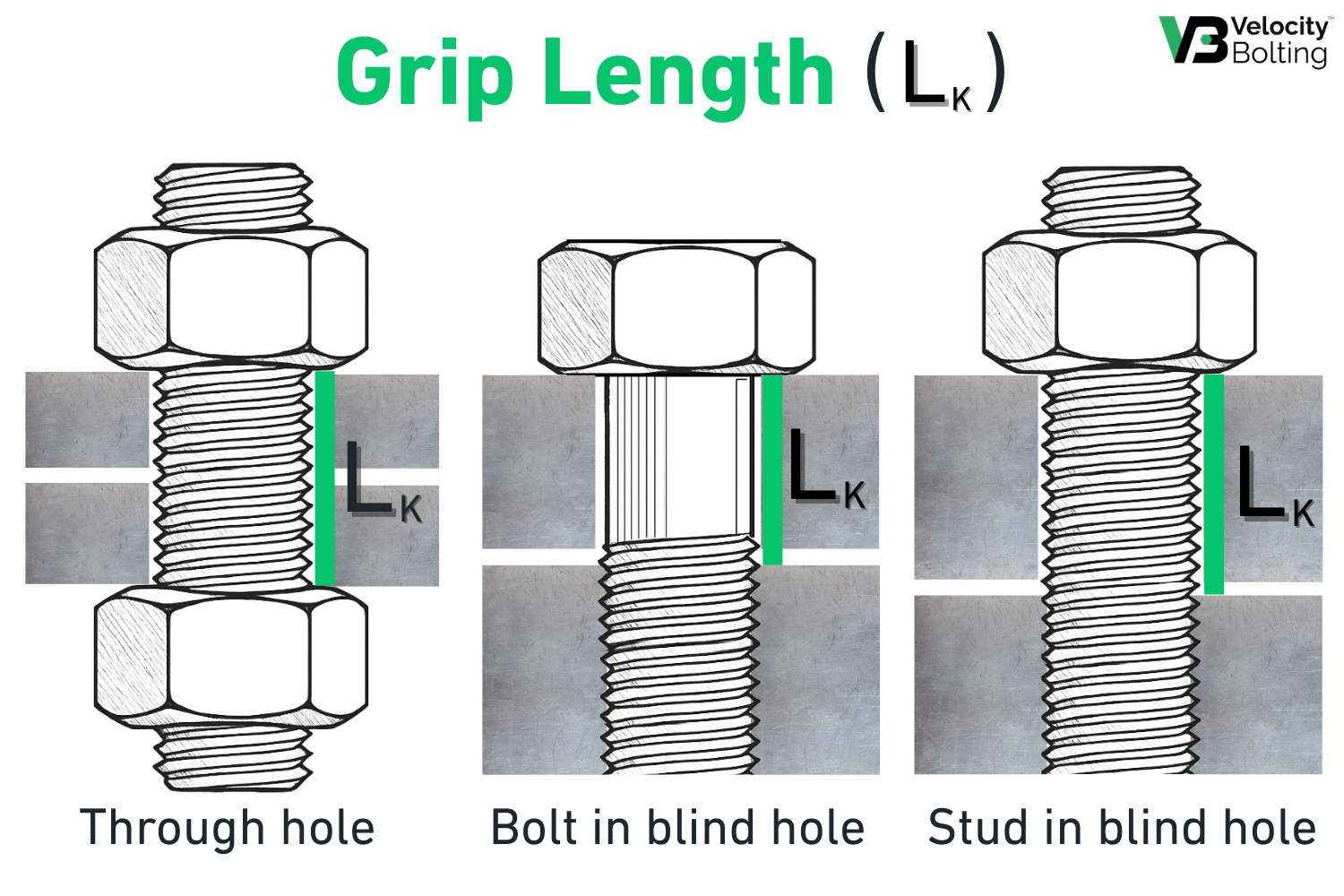

Understanding Grip Length in Bolts and Studs

In bolted joints, grip length is a critical design parameter that directly affects joint integrity and performance. Simply put, grip length is the total thickness of the materials a fastener (bolt or stud) clamps together.

Why Use Washers? A Technical Guide to Washer Types (Standard, Hardened, Belleville, Lock, and Velocity)

Washers may be small and often overlooked, but they play a critical role in bolted joints. In engineering applications, using the right washer can mean the difference between a reliable connection and a failed assembly.

From Shutdown to Startup: How Bolt Failure Impacts Plant Turnarounds

Plant turnarounds – those planned shutdowns for maintenance and inspections – are high-stakes events in the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries. Every day of downtime is carefully scheduled and extremely costly. Yet, despite meticulous planning, something as small as a bolt can throw an entire turnaround off track.

What is a Velocity Washer?

What is a Velocity Washer? Learn more about the what, why and how of the technology in this post.

Why Stainless Steel Experiences Thread Galling More Frequently Than Other Metals

Critical Flanges: Advanced Washers Eliminate Galling and Hot Work (Chemical Engineering)

This article was originally published in Chemical Engineering in November 2022.

Galling: The Hidden Enemy of Heat Exchangers

Heat exchanger maintenance often comes with a frustrating challenge: bolts and nuts that seize up during disassembly. This seizure is usually caused by a phenomenon called thread galling – essentially a form of “cold welding” between the threads.

Why Galling Occurs on Threaded Fasteners

Hydraulic Bolt Torquing vs. Bolt Tensioning: What is the difference?

Hydraulic Bolt Torquing vs Bolt Tensioning: What is the difference?

Single Stud Replacement: An (ineffective) method to deal with galling

A comprehensive guide to single stud changeout (also known as “hot bolting”). We’ll cut to the chase: if you want to avoid all the headaches and safety issues related to single stud changeout, just use Velocity Washers.

The Galling Phenomenon: What exactly is galling?

Galling is a common mechanical phenomenon encountered during the fastening or disassembly of threaded components.