Bolt Tension vs. Bolt Stress vs. Clamp Load: What Engineers Actually Mean

Plant engineers and maintenance supervisors often hear terms like bolt tension, bolt stress, and clamp load used in discussions about bolted joints and flange assemblies. These terms are related but not identical – and mixing them up can lead to confusion or even maintenance mistakes. In this post, we’ll clear up the differences using field-relevant terms, practical analogies, and real-world flange examples. By the end, you’ll know exactly what engineers mean by each term, why they matter for keeping joints tight and leak-free, and how misconceptions about them can be avoided. Let’s dive in!

Defining the Terms Clearly

Before we get into analogies and applications, let’s define bolt tension, bolt stress, and clamp load in clear terms:

Bolt Tension (Preload): This is the axial force stretching a bolt when you tighten it. Think of bolt tension as the “pulling force” in the bolt – the result of turning a nut or tightening the fastener. In bolting lingo, tension is often called preload (the load introduced to the bolt before any external loads). When you apply torque to a nut and bolt, the threads act like a ramp and the bolt elongates like a stiff spring, developing tension while simultaneously pulling the joint pieces together. For example, if you tighten a bolt and create 20,000 pounds-force (lbf) of tension, that means the bolt is being stretched with a 20,000 lbf internal force trying to return it to its original length.

Clamp Load (Clamping Force): This is the compressive force squeezing the joint parts together as a result of the bolt tension. When the bolt stretches under tension, it clamps the connected flanges or plates together with an equal force – this is the clamp load. In fact, in a static, tightened joint with no external loads, the bolt’s tension is equal and opposite to the clamp force on the joint. You can picture the bolt acting like a stretched spring pulling the components together, while the components act like a compressed spring pushing back with the same force. Clamp load (sometimes just called “preload” as well) is what actually holds a gasketed flange together and prevents leaks. If our bolt has 20,000 lbf of tension, then 20,000 lbf of clamp force is squeezing the flanges and gasket together – they are two sides of the same coin.

Bolt Stress: This refers to the stress inside the bolt material due to the tension – essentially the tension force divided by the bolt’s cross-sectional area (at the threaded section). Engineers usually express bolt stress in units like psi or MPa, and it’s a way to quantify how close the bolt is to yielding or overstressing. For instance, a bolt tension of 20,000 lbf in a 7/8-inch diameter stud (with ~0.462 in² stress area) results in about 43,300 psi of stress in the bolt. Bolt stress is often specified as a target in bolt-up procedures – e.g. “tighten those flange studs to 50,000 psi bolt stress.” This simply means apply a tension that, given the bolt size, corresponds to a calculated stress level. In industry, “bolt stress” or “rod stress” is a convenient way to communicate preload requirements, since it relates to material yield. (For example, 50,000 psi is roughly 50% of the yield strength for common B7 stud bolts.) In summary, bolt stress is not an additional force or something separate – it’s an internal measure of the same tension, normalized over the bolt’s area. We care about it because bolts have finite strength; too high a stress and the bolt yields or breaks, too low and we aren’t using the bolt’s strength effectively.

Bolt Tension vs. Clamp Load: The Spring Analogy

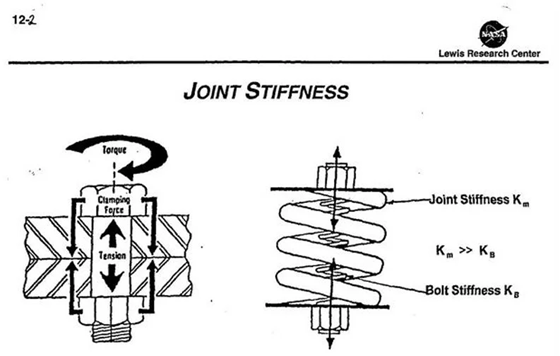

It’s crucial to understand that when a bolt is tightened, the bolt and the joint act like two springs in series – one stretching (the bolt) and one compressing (the clamped parts). The tension in the “bolt spring” always equals the force in the “joint spring.” In other words, the bolt’s tension is the clamp load holding the joint, just viewed from the bolt versus the joint perspective.

Illustration: The bolt (left) stretches like a spring under tension, while the joint (right) compresses like a spring under the clamp load. The force in the bolt is equal and opposite to the force compressing the joint.

As you tighten a flange bolt, imagine placing a very stiff spring under the nut – as you turn the nut, the spring (bolt) is pulled upward, and the flanges (joint) are squeezed like another spring. The more you tighten, the more tension in the bolt and the more clamp force squeezing the flanges together. If you stop tightening at (say) 20,000 lbf tension, the bolt is pulling up with 20,000 lbf and the joint is pushing back with 20,000 lbf of compression. They are in balance. This is why bolt tension and clamp load are often used interchangeably in casual conversation – they refer to the same magnitude of force, just acting in opposite directions on different parts.

Real-world analogy: Think of using a C-clamp or vise to hold two pieces of metal. As you turn the screw, you are effectively “tensioning” the screw (stretching it slightly) and that produces a clamping force on the pieces. The tighter you turn the screw, the more the screw stretches and the harder the jaws clamp the pieces. The screw’s tension = the clamp force on the workpiece. A bolted flange works the same way, except the stretching and compressing are microscopic (you won’t visibly see the bolt get longer or flange get thinner, but it’s happening on a small scale).

One implication of this spring-like behavior is that if the joint material is much stiffer than the bolt, most of any extra load (like pressure trying to separate a flange) goes into stretching the bolt a bit more rather than opening the joint. Ideally, we tighten bolts so that the clamp load is higher than any forces trying to separate the joint during operation. That way, the external load first just relaxes the clamp slightly rather than immediately yanking the bolt further. (This is like preloading a spring scale with a 150 lb block: any smaller weight you add doesn’t change the spring reading until you exceed 150 lb.) As long as the external loads never exceed the preload, the joint won’t separate and the bolt won’t see significant additional stress on and off – which is great for fatigue life.

Bolt Stress: Why Engineers Talk in PSI

As mentioned, bolt stress is essentially a way to talk about how tightly a bolt is stretched in terms of the material’s capacity. Technically, stress = force / area. If we know the desired clamp force and the bolt size, we can calculate the stress in the bolt. Engineers often find it convenient to specify a bolt-up in terms of stress because material specs (like yield strength, proof load, etc.) are given in stress units. For example, a common material for refinery and plant flange bolts is ASTM A193 Grade B7, which has a yield strength around 105,000 psi. A typical assembly might target around 50–60% of yield for preload to be safe – say 50,000 psi bolt stress. This means each bolt is tightened such that the tensile stress in its cross-section is 50,000 psi, well below yield. For a 7/8" stud (stress area ~0.462 in²), that corresponds to roughly 23,000 lbf of tension (and clamp load). For a 1" stud (stress area ~0.606 in²), 50,000 psi means about 30,300 lbf of force.

Why not just specify the force? In design calculations we do use the force (e.g. required clamp load for a gasket), but when communicating to technicians or across different bolt sizes, psi is more universal. Bolt stress lets us say “tighten all those bolts to X% of their material strength” without worrying about the exact diameter in that sentence – the conversion is handled when doing the torque or tensioning calculations. It’s also how hydraulic tensioners are often calibrated: e.g. apply pressure until the bolt sees 40,000 psi stress, etc.

Importantly, bolt stress being too high or too low has consequences:

If the stress is too high, the bolt may yield (permanently stretch) or even break. Over-stressing can also crush gaskets or damage flange faces. For instance, going to 100% of yield (105,000+ psi on a B7) is usually a bad idea – most procedures limit to ~70% of yield max (around 73,500 psi for B7). Standards and torque charts typically base recommended torque on about 75% of the bolt’s proof load (a proof load is typically ~90% of yield). This provides a safety margin so the bolt stays elastic. Exceeding that can lead to necked or broken bolts, and in the long run, possible stress corrosion cracking in certain environments.

If the stress (preload) is too low, you haven’t clamped the joint enough. The bolt might not be fully engaging the friction needed to prevent movement, so the nut could loosen under vibration, or the flange could leak under pressure. A loose bolt will also see larger stress fluctuations if the joint gaskets breathe or an external load comes, which can cause fatigue failure. Many flange gasket failures are due to insufficient preload – the bolt stress was below what was needed to keep the gasket compressed against internal pressure. This is why guidelines often specify a minimum bolt stress as well (to ensure a tight joint). In short, there’s a Goldilocks zone: not too low, not too high – just right for the application.

A common industry target for many steel bolts is to aim around 50–70% of yield stress for preload, which balances these concerns. Always refer to specific joint engineering or standards (like ASME PCC-1 for pressure vessels) for the right numbers, but the concept holds universally.

Practical Flange Assembly Implications

In everyday flange assembly and maintenance, understanding tension, stress, and clamp load is critical:

Achieving Proper Gasket Load: Flanged pipe joints rely on sufficient clamp load squeezing the gasket. If you miscommunicate and only apply (for example) a certain torque that results in too low a tension, the clamp load may be insufficient and the flange could leak or blow out the gasket. Knowing that torque is just a means to generate tension (preload) is key – the torque itself isn’t what holds the joint, it’s the tension it hopefully creates in the bolt. In fact, torque is only a means to an end – the end is preload (clamp load). This means crews must ensure their tools, lubrication, and procedures actually achieve the target tension. About 50% of tightening torque is typically lost to under-head friction and ~40% to thread friction – only ~10% of the torque actually goes into stretching the bolt as tension. Small changes like a different washer finish or using lubricant can swing the achieved tension by 30-50% for the same torque input. Misconception alert: It’s wrong to assume a specified torque will always produce the same clamp – factors like thread condition, lube, and surface finish matter a lot. Always use the specified K-factor or coefficient in torque calculations, and whenever possible, use controlled methods (like tensioners, or at least calibrated torque wrenches and bolt lubrication) to get consistent tension.

Sequence and Elastic Interaction: On large flanges with many bolts, tightening one bolt can relax others (as the joint stretches and redistributes load). This is why we follow criss-cross tightening patterns and multiple passes. The goal is to bring the whole joint up to an even tension. If someone doesn’t understand clamp load, they might think “I tightened each bolt to X torque, so we’re good.” But if the sequence was wrong, some bolts might be significantly under-tensioned due to joint settling. Knowing that it’s the final tension that matters, smart assemblers measure bolt elongation or use load-indicating washers for critical joints to verify the actual tension achieved, rather than blindly trusting torque.

Avoiding Overload and Flange Damage: Over-tightening (too high bolt stress) can be just as bad as under-tightening. An over-tensioned bolt can yield and lose its ability to clamp (like a stretched spring that doesn’t spring back). It can also impart excessive compressive force on the flange faces, warping them or crushing the gasket. An old misconception is “tighter is always better” – in reality, the largest preload force possible is not the best. You want just enough clamp to hold against service loads with a safety margin, but not so much that you introduce new problems. This is why bolting specs limit the torque/stress. Bolts are designed to operate in their elastic range; if you take them past yield, you’ve essentially turned that fastener into a permanently stretched noodle that may unload or break. One field tale from a maintenance shop: A technician, thinking more torque equals more safety, over-tightened a heat exchanger flange. The bolts yielded (bolt stress exceeded yield strength), and when the exchanger heated up in operation, several bolts actually fractured. The joint leaked and had to be taken out of service – exactly the opposite of the intended “safety”! The bottom line is to use the correct tension, not simply maximum muscle.

Monitoring Clamp Load Over Time: In service, bolts can lose tension due to relaxation, creep of gasket, or thermal expansion differences (the joint “settles” or expands/contracts). This loss of preload means loss of clamp load. Good practice is to re-check flange bolt tightness after initial operation (hot/cold cycles) or use load-indicating devices. Understanding that a drop in bolt tension directly means a drop in clamp force on the gasket helps maintenance prioritize bolt inspection in critical joints. If a flange starts to weep, the first suspicion is that clamp load (hence bolt tension) has diminished or wasn’t enough to start with.

Real-World Analogies & Misconceptions

It helps to use analogies to visualize these concepts, and to address some common misconceptions in the industry:

Bolt as a Stretched Spring, Joint as a Compressed Sandwich: We’ve used the spring analogy – this is a favorite in training. Another analogy: imagine a strong rubber band (the bolt) holding a stack of books together. The rubber band is under tension (stretched), and the books are under compression (clamped). If the band is too slack, the books can slide apart (like a loose flange leaking). If the band is too tight and not strong enough, it might snap (bolt breakage). The proper tension in that band keeps everything snug and secure.

Torque vs. Tension (Friction is the Wild Card): It’s worth reiterating the torque misconception because it’s so prevalent. Maintenance folks often speak in terms of tightening torque because that’s what the wrench reads. However, two identical torque values can result in very different bolt tensions if one bolt was well-lubricated and another was rusty or dry. The friction difference means one bolt might get much less tension from the same torque. A classic saying: “Turn-of-the-nut” is a crude method – about as accurate as ±25-30% on tension. Modern methods like torque + angle, or direct tension indicating (DTI) washers, or ultrasonic measurements are used in critical joints to ensure actual tension. The key misconception to avoid: torque is not a direct measure of clamp load – it’s an indirect proxy. Always account for friction and use calibrated data. In practice, this means if someone says “we need more torque on that bolt,” the question is why? If the joint is leaking or loosening, perhaps the issue is that the achieved tension (clamp load) was too low, not that a specific torque number is magic. Focus on ensuring the right tension, whether by recalibrating the torque or using better lubrication.

Units Confusion – lbf vs ft-lb: Another simple but important clarification in communication: bolt tension/clamp load is a force (lbf or kN), whereas torque is a twisting moment (ft-lb or N·m). It’s not unheard of for a less experienced tech to say “I put 100 foot-pounds of force on that bolt” – mixing units. Foot-pounds (or Newton-meters) measure the wrench effort, not the straight-line force in the bolt. So always ensure when someone references a number, it’s clear if they mean the torque or the actual tension. For example, “150 N·m” and “150 kN” are vastly different – one is torque, one is force! Misstating one for the other can be dangerous. Good documentation and training make sure everyone speaks the same language of either torque or tension as needed.

“Preload + Service Load” Misunderstanding: In a properly designed joint, you don’t simply add the preload and the external load to get total bolt load – at least not until the external load starts overcoming the preload. Some mechanics might think “if the bolt has 10,000 lbf of preload and 5,000 lbf tension from pressure, that’s 15,000 on the bolt.” Actually, if the joint remains closed, much of that 5,000 is taken up by reducing the clamp on the gasket rather than all going into the bolt at once. The bolt may only see a portion of an external load initially. The correct view (per elasticity and joint diagrams) is the bolt doesn’t feel the full external load until the clamp load is completely overcome. So a well-preloaded joint can resist a working load without the bolt stress fluctuating fully with that load. The misconception here is more on the analytical side, but it underpins why we preload bolts in the first place – to protect them from cyclic loads.

“Stronger Bolts = Automatically Better”: Upgrading to a higher grade bolt (say from grade 5 to grade 8, or B7 to stronger B16) but then tightening it to the same tension as before doesn’t necessarily improve anything and can even reduce reliability. If you don’t actually utilize the higher strength by increasing preload (which you may not due to gasket or flange limits), you just end up with a stiffer, more brittle bolt that isn’t any less likely to loosen. Using a stronger bolt material with the same assembly torque/preload can be counterproductive – the stronger (often harder) bolt can be less ductile and more prone to brittle failure if not loaded properly. The lesson: choose bolt material based on needed preload and environmental factors, and use it appropriately; don’t just assume swapping in stronger bolts without other changes will magically solve joint issues.

“More Bolts or Bigger Bolts for Security”: Similarly, adding extra bolts or upsizing a bolt isn’t always the best solution to a loosening problem – ensuring correct preload on the existing bolts often is. A well-preloaded joint might do fine with fewer bolts, whereas a poorly preloaded joint can fail even if you double the bolts. It’s the clamp force that matters. This misconception isn’t about the terms per se, but it’s a reminder that the quality of tension is more important than sheer quantity of hardware in many cases.

The Velocity Washer Example: Tension Control in Maintenance

As a brief real-world example (and a nod to a technology in use today), consider Velocity Bolting’s Velocity Washer, a patented mechanical release washer. This is not the focus of our discussion, but it nicely illustrates how understanding bolt tension and clamp load leads to innovative solutions. The Velocity Washer is a patented mechanical washer that sits under a standard nut. During tightening, it behaves like a normal hardened washer (so you achieve the required preload on the bolt as usual). But during loosening, it does something special: after just a small turn (about 12°) of the nut, the Velocity Washer “pops” and releases all the tension (clamp load) in the bolt at once. In essence, it’s a quick-release for the bolt tension. Why is this useful? Because it prevents galling – the notorious seizing of nuts on bolts.

In normal disassembly, you have to spin a nut many turns while the bolt is still stretched (tensioned) against it. All that sliding under high pressure causes heat and metal transfer (thread galling), especially in stainless steels or large, fine-threaded fasteners. With the Velocity Washer, the first small turn instantly drops the clamp load to zero, so the nut is no longer pressed hard against the threads. The nut can then be spun off freely by hand or with a light wrench – no galling, no fighting the tension. Maintenance crews have found that by swapping a standard washer for a Velocity Washer, they can eliminate seized nuts and remove bolts up to 30× faster than usual. In fact, this technology has a documented 100% success rate in preventing galling in all its installations worldwide.

For a plant engineer, the key takeaway is how it emphasizes the role of bolt tension in disassembly. The Velocity Washer doesn’t make the bolt any stronger or the torque any lower; it simply manipulates when the tension is present. It holds the tension during operation (keeping clamp load like any washer would), but on cue, it lets that tension go at the right moment. This highlights an important point: bolt tension isn’t just a factor when tightening – it matters throughout the bolt’s service life, including how you safely remove it. Galling and seized bolts often come from residual tension during loosening; a better grasp of clamp loads led to a solution that improves safety and saves time. (Imagine not having to bring out the grinders or blowtorches to cut off frozen nuts – as some crews must do after a bolt has galled. A faster turnaround with less risk and no destroyed studs is a big win for maintenance supervisors.)

While most of us won’t need a Velocity Washer on every joint, it’s a good example of how getting the tension/clamp load right and controlling it can solve practical problems. It’s certainly something to keep in mind for critical or chronic problem flanges where galling or long disassembly times hurt your uptime. The broader lesson is that innovations in bolting focus on managing tension and clamp load more effectively – whether it’s hydraulic tensioners, load-indicating washers, improved lubricants, or devices like this washer, they all come back to controlling that fundamental preload force.

Conclusion

In summary, bolt tension, bolt stress, and clamp load are closely related terms but distinct in meaning:

Bolt tension is the actual force trying to stretch the bolt (the preload we apply with tightening).

Bolt stress is how that force translates into the bolt material’s internal pressure (force per area), often used to compare against material strengths or specify tightening in a normalized way.

Clamp load is the force squeezing the joint parts together as a reaction to the bolt’s tension, the benefit we seek from tightening the bolt.

They are different ways of describing what happens when you tighten a bolt, and understanding each one helps you as an engineer or supervisor ensure joints are assembled correctly and safely. The bolt’s tension (preload) is what we input, the clamp load is what we get to hold our equipment together, and bolt stress is like the “gauge” reading telling us how hard we’re pulling on the fastener relative to its capacity.

By clearly differentiating these terms, we avoid miscommunication. For example, saying “we need X psi on those bolts” (bolt stress) versus “we need X kN clamping force” versus “tighten to X N·m torque” can each lead to the correct outcome, but they are not one and the same. Now you know the relationships: torque → tension → clamp load, all while keeping an eye on stress.

Always remember: a well-preloaded (tensioned) bolt that stays in elastic range is the unsung hero preventing leaks and loosening. Use the proper torque or tensioning method to achieve the desired bolt tension, verify the clamp load if you can, and stay within safe bolt stress limits. With this knowledge, next time someone loosely says “make sure those bolts are tight,” you can confidently reply “Absolutely – we’ll torque them to get the correct tension and clamp load, without exceeding our bolt stress limits.” That’s what engineers actually mean.

Statics and dynamics aside, a sound bolted joint ultimately comes down to managing that triad: tension, stress, and clamp load – now you’re equipped to do it right.

______

Disclaimer:

Portions of this article were generated with the assistance of ChatGPT, a large language model developed by OpenAI. The content is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute professional, legal, financial, or academic advice. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the author, and readers are encouraged to independently verify any information presented.

The AI-generated content has been reviewed and edited for clarity and accuracy where appropriate.